When it comes to AMC’s megahit Breaking Bad, there are really three types of people. The first are those who have crossed the final threshold of suspense in the series finale, whether they arrived there via the steady and loyal consumption of five years of broadcast or, like myself, via binge-watching. The second are those who are still wandering somewhere in the middle of the show’s vast desert, wondering as they wander how much worse the stress can actually get (and yes, it keeps getting worse). The third are those who have not watched and do not really know (or care) what all the fuss is about. This analysis—originally composed just on the other side of the show’s conclusion—is written for all three audiences. For the first, I am attempting to offer some insight into what we have witnessed. For the second, I am attempting to provide some possibilities for deeper viewing. And for the last, I am giving you either a final excuse to definitively pass on the show or some incentive to watch it, depending upon your preference. For the second and third types, I assure you that this article will not spoil your future viewing even though I obviously have to talk about the show to analyze it.

Breaking Bad is simultaneously a simple and complex drama. The simplicity of the show is held in the interconnected multiplicity of storylines within one overarching story, which, for the most part, generates the drama of the narrative organically (as opposed to other shows which are constantly having to introduce new elements to restart otherwise stalled stories). The complexity of Breaking Bad comes from the depth of its exploration of the human psyche, the moral fabric of communities, and the relationships that bind people together, for better or worse. This multi-layered, unified drama opens up in three major, interlocking themes, which will guide our analysis: pride, responsibility, and the social nature of humanity.

Pride

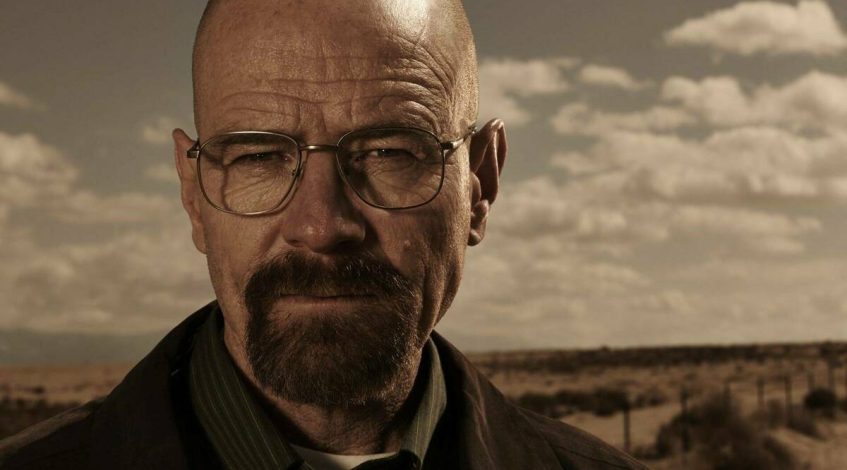

If nothing else, Breaking Bad is a sustained meditation on pride as the will to reorder reality according to one’s own desire. Behind all its many disguises, this desire seeks self-perpetuation and self-aggrandizement. The harbinger of this desire is the “lie,” for what is lying but the dismissal of true reality by the willful manipulation of others through a false narrative. While there are almost always mitigating factors behind the act of lying, at its core, lying allows one of the participants of a human drama to become that drama’s author in some way, thereby assigning other participants new roles within a new script. For those who have watched even a few episodes of Breaking Bad the pathology of lying is well known as a pervasive element in the story.

Since the third-to-last episode of the series brings the story to its climax, it comes as no surprise that the main theme of pride and the correlative action of lying are both restated and definitively interpreted. The opening scene of the episode finds Walter and Jesse—the drama’s primary and secondary characters, respectively—back at the beginning of their entrepreneurial days as aspiring methamphetamine producers. The scene is not exactly one that appeared in a previous episode but nevertheless fits perfectly within the narrative sequence of the show’s early days. Since a number of storylines will come to a head in this episode, the writers used this opening sequence to remind the viewers what is holding this all together. Waiting for a beaker of boiling chemicals to reach its own climax, Walter gives his former failing student (Jesse) a quick lesson on exothermic reactions: chemical processes that give off heat and whose effects move in an outward trajectory. At the close of the scene, Walter steps away to call his wife and offer the first direct lie of the entire story. Except for the mobile meth lab just over his shoulder, the lie seems rather ordinary as he basically says, “Honey, I’m going to be late tonight because something came up at work.” Thus begins the chain reaction.

By the fifth season, viewers may have forgotten just how bad Walter was at lying in the early days. Before that first lie, we see him rehearsing his story; even more importantly, he justified it to himself based on his particular circumstances. There would always be justifications and, before long, others would justify their own complicity in his corruption, whether knowingly or unknowingly. Seen from the distance of five seasons (or less than two years within the show’s own timeline), that first lie now reveals itself as an initial, awkward move to recast events according to a desire to manipulate reality. As his pride grew and hardened, Walter’s lies became more “natural” and more ingrained. Paradoxically, the more Walter reworks his reality, the stronger the force of destiny surrounding him becomes. With each passing episode in each passing season, the air of inevitability grows ever stronger. The more power Walter accrues through the willful warping of his reality, the less free he actually is to control his reality and wield events to fit his desire. More and more, the destiny he constructed controls him.

The title of this climactic episode also discloses something essential about the show’s meta-theme. The writers borrowed its name from the Percy Bysshe Shelley poem, “Ozymandias.” The final third of the poem reads as follows:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings,

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far way.

With the almost obsessive attention given to Walter White through more than sixty episodes of Breaking Bad, it is easy and perhaps fitting to think of Walter as this “King of Kings.” If, however, we consider how Walter’s own freedom has slowly evaporated into the encircling gloom of destiny as the heat of his pride steadily increases, we might ponder more deeply who inscribed these words on the remnant sculpture that Shelley depicts in this sonnet. With the passage of time, the reaction that started with a simple lie and a heart of mixed motives has now brought about a reality that seems inevitable in retrospect. The one who tried to sculpt a reality for himself is now rendered an artifact of that very reality. The King who outlasts all kings is that hardened destiny born of pride.

If this destiny is the child of pride, then Walter nourished this impersonal despot from infancy. He fed it the envy he reaped from gazing upon the accomplishments of others. He offered it outrage from an ongoing sense of being cheated. He suckled it with fury for his underappreciated genius. As his pride grew from a singular lie to a pattern of lying to an unending urge for control, he finally glimpsed what his desire had become: a compulsion for empire—that is, for the unbridled aggrandizement of himself as undisputed sovereign of his realm.

Responsibility

With a character as central to a story as Walter White, it is tempting to place the genesis of the drama in his own psyche. Part of the brilliance of Breaking Bad is that it does not easily allow for this contraction. What the viewers see through both the sequence of events and the ultimate interconnectedness of these events is that even a colossally dominant figure like Walter is not a monadic entity. He is not just himself. The choices he and others make throughout the course of the drama are constitutive of Walter’s total embodiment. Though the events of this particular show take place in a highly charged crucible of time and space, there is also a claim here about universal human personhood: we are responsible for our choices just as we make manifest in our very selves the responsibility others have for their choices.

Each character in this story—including and especially Walter White—both lives in and contributes to a certain reality that correlatively orders them and is ordered by them. As with any story, the characters inhabit an order that is already established before we meet them. They exist in a certain socio-historical setting replete with undergirding pasts of pains and joys, successes and sorrows, and possibilities realized and unrealized. What this drama does better than most (perhaps all) in television history is show how these particular characters—and again, especially Walter White—shape their previously preordained milieu through their intentions, actions, interactions, and failures to act. Each of them comes to change not just on account of some interior disposition—whether given or chosen—but through the tension found between their interior disposition and their exterior relation to their environment, especially their relationships to one another. What the viewer comes to see is that what holds together in each person is more than what each person knowingly holds. To again refer to the key chemical term, their choices set off exothermic reactions that reach outwards to others even as others’ choices reach out to them.

This means that the full view of each individual person surpasses what one can see by looking just at the individual. One cannot know Walter White or Jesse Pinkman through psychology alone. Indeed, each character is involved in the construction of an economy, one in which all share. This economy houses transactions in terms of blessings and curses, mercies and deceptions, kindnesses and lies. Of course, there is also a tremendous amount of money, drugs, and power in circulation. Each one of the characters’ chosen actions—regardless of the degree of freedom involved in their discharge—creates a shared reality in which the choices of others are conditioned. While no one inside the story sees all of these connections, the viewer does (or at least “can”). From the other side of the screen, the viewer is able to see how the historical expressions of the characters’ disparate desires extend who they are into the lives of others. Certainly, Walter White (or Heisenberg) exists beyond the limits of his physical body, but so too does Skyler White, Hank Schrader, Jesse Pinkman, and all the other major characters in the drama.

Therefore, each character’s personal responsibility extends broadly in all directions. For those who might be interested in questions of judgment and redemption, the field of vision required to level judgment and evaluate prospects for redemption is almost infinitely vast. For sure, each person’s responsibility outlasts the action itself; in fact, responsibility endures even after one’s own life, since the full measure of one’s choices continues to unfold well after one’s death (this is a general statement rather than a statement about any particular character: again, no spoilers here about who does or does not die). Once a choice ratifies an interior desire and is discharged into the shared economy of persons, that person is at least to some extent responsible for the consequences, for good or for ill.

Social Nature

What we see in Breaking Bad is that the bonds between people are conductors. What one person does or wills reaches out through their relations into a broader network: a social network. The familial community at the center of the drama discloses this truth in an acute fashion. As one person curves his will inward to suit his own purposes, he affects and influences the rest of the family members. It is not just the consequences of Walter’s pride that spread; pride itself spreads. Under the strain and stress of one person’s incurving concern, each member of the network begins to abide in a new reality, one in which the rule of pride is infectious. Whereas we were introduced to this family as a community of mutual concern—for all intents and purposes—we watch them slowly deteriorate as the dilemma and deception Walter introduced make it impossible for others to care for him—or one another—authentically. Even before Walter’s lies are uncovered, the lies separate him from authentic participation in the community. This distance causes uncertainty and even fear, causing the other members to recoil in anxiety without even knowing what it is they fear. Corrosion seeps into otherwise unperceived places, compromising even the best of intentions.

That these persons are connected and that their connections act as conductors are both givens in the narrative. This makes the corruption of one person even more dangerous because it means that the other persons in relation to him are interiorly affected in addition to being exteriorly influenced. Yet, for all the ways in which this social nature compounds the crisis of pride, it also remains an implicit grace.

On the one hand, even the man at the source of the corruption—Walter White—is unable to exercise an absolutely evil will because of the ties that unite him to others. Without his connections to his children, his wife, and even to Jesse Pinkman—for whom he develops an almost inexplicable paternal fondness—Walter very well may have purely willed his selfish way regardless of the consequences. As corrupted as his care becomes, he does care for these few others and thus is never able to will pure destruction. This enduring grace ultimately thwarts his success at building his empire, at becoming radically evil. If those who have seen the show think of the times when Walter either could have or tried to “get out” of the “empire business,” one will see how his ambition is at least distracted because of his connections to others.

On the other hand, this social nature is an implicit grace because just as pride was communicated through the network, so too is sacrifice communicated. Viewers see moments of mercy from Walter and Jesse beginning even in the early episodes. Certainly, these mercies are communicated socially. The problem is that the crisis of pride has reverberated so strongly that these mercies call for greater ones in order to endure and have lasting effects in the corrosive economy.

Breaking Bad clearly shows that the social nature of humanity works to communicate corruption, but the show also quietly implies that this network would communicate blessing. This social nature impedes Walter from willing definitively—in a single instant, like a fallen angel—his identity. His choices always enter into the social network just as they are always conditioned through it. His pride will move through the network so long as his pride festers, but his own sacrifice might also become the source of healing for his wounded family albeit without the power to immediately right every wrong.

The Singular Question

Of course, it is pride that drives this chaotic narrative from beginning to end. The show’s drama builds as pride’s leavening effect is first unleashed and then progressively gathers strength. St. Paul knew this well in his own communities: “Do you not know that a little leaven leavens all the dough?” (1 Cor 5:6). Through the highly concentrated drama of the particular circumstances of Breaking Bad we see the truth of this statement. The hidden possibility of redemption thus runs alongside this accelerating tragedy, with the implicit invitation rising to the surface at key moments through Walter’s conscience, his relationships, and his occasional exhaustion, as if to say, “Let us, therefore, celebrate the festival, not with the old leaven, the leaven of malice and evil, but with the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth” (1 Cor 5:8).

The question of the entire series is, thus: will Walter White perpetuate his pride—that addiction to controlling his reality that serves as leaven and chemically induces the growing certainty of the tragic destiny—or will he hazard himself in a sacrifice of truth and humility where he releases control, thus removing the leaven, come what may?

EDITORIAL NOTE: Join us on Friday, May 5th and Saturday, May 6th for McGrath Insitute’s conference “Gilligan’s Archipelago: Justice and Mercy in Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul.”

Click here for more information. No registration required.