Brett Robinson: Hello, world! The advent of ChatGPT (on its fourth iteration as of this week) and generative AI has introduced some vexing questions about the role of language in online environments. How do we know who’s “speaking?” A person or a machine? What do authorship and originality look like in this new world? The panic among educators who fear a new wave of plagiarism is somewhat justified but it risks missing a deeper point and a possible opportunity.

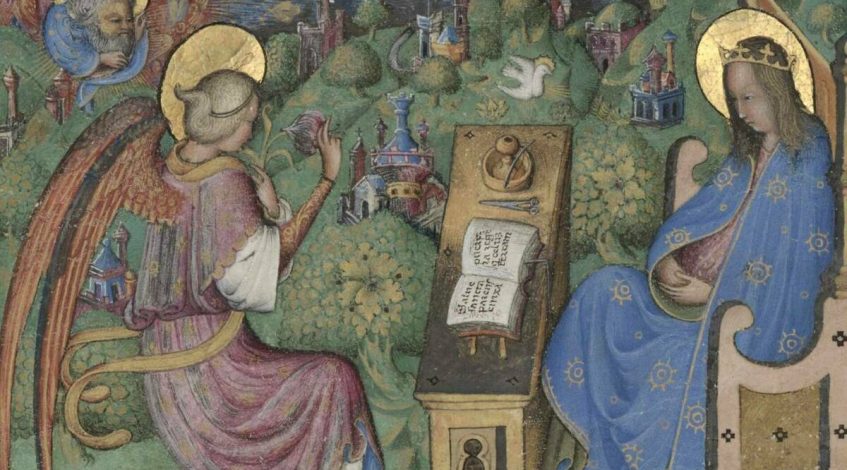

Fr. John Culkin said, “We shape our tools and, thereafter, our tools shape us.” As we enter into a more intimate mimetic feedback loop with our prosthetic brains, it may be time to reconsider the cultural authority of the “essay,” an artifact of the printing press. If essays can be replicated or imitated by the evil media of AI, then perhaps humans should think more medieval-ly. That is, recover and renew the oral traditions of conversation and disputation that characterized philosophical reflection for much of the pre-print era going back to the Greeks.

Plato’s Phaedrus foreshadows our current predicament when Socrates challenges Lysias on the relative value of a written speech versus one delivered from memory. In a story about the gift of writing being invented by the Egyptian god Theuth, Socrates delivers a condemnation of writing that could also be applied to both the internet and generative AI:

It will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory. Their trust in writing, produced by external characters which are no part of themselves, will discourage the use of their own memory within them. You have invented an elixir not of memory, but of reminding; and you offer your pupils the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom, for they will read many things without instruction and will therefore seem to know many things, when they are for the most part ignorant and hard to get along with, since they are not wise, but only appear wise.

Marshall McLuhan said that when faced with information overload, “we have no alternative but pattern recognition.” The problem is that pattern recognition is precisely how generative AI manages to fool us into thinking that a human could have written the text we see on screen. In other words, we have outsourced pattern recognition to the machines, placing us at their mercy when it comes to making sense of “too much information.”

In the following discussion, three participants from the McGrath Institute’s Church Communications Ecology Program, a philosopher, a journalist and an English teacher, turned the tables on the machine. Their conversation, recorded over ZOOM, was transcribed by Descript and edited by AI software that could detect the voices of the speakers. The conversational format is intentional as it playfully avoids the essay form in favor of a more pre-modern medium of human exchange, the live conversation (mediated by computers, of course). Hopefully the following inspires even more conversation (among humans) about how to better understand what is happening to language and culture and what it means to be human in the first place.

Bo Bonner: All right. Take it away.

Renée Roden: I think something we get wrong is the ground of artificial intelligence (AI). We have this image of AI being a sentient force. We think of AI as being human when, rather, it’s just a level of computing that we’ve reached. A level of computing which is a difference of degree, not kind. But it seems like we’re approaching a difference of computing that’s a difference of kind rather than simply degree.

ChatGPT seems like a new, exponentially greater power of computing, and it’s presented in a very humanoid way, right? It’s linguistic computing that you can dialogue with.

It seems to approximate a human brain and a human relationship. But ChatGPT is not speaking in sentences, it’s speaking in an algorithm that guesses the words that follow each other in a typical human sentence or in the number of sentences that have been fed into its databases. And, this is something you’ve talked about, Bo. Its writing is so unoriginal and cliched, because it’s built from averages, right?

Cliched writing is not actually describing in fresh detail the particularity that I see in front of me, it’s cribbing what other writers have said about other similar things. I feel like ChatGPT often comes out as very bland and cliched because it’s really just an average of human language.

It writes like students who aren’t learning how to explore their own subjectivity or express it in a tradition. They write through cliches and imitation, not their own experience. So ChatGPT in some ways mirrors the state of education and the state of writing.

Bo Bonner: That’s why everyone’s like, “We’re going use the robot to write Buzzfeed.” And everyone’s like, “That makes sense.”

I think what’s really interesting is what you’ve brought up, Jane. Everything we’re saying at this dorky philosophical level is deeply true, but why is it hard for students to see that?

That’s the mystifying nature of all this in terms of education: figure/ground stuff, right? We get really caught up with content creation, “original content,” but weirdly, language itself is always imitative. To learn or use a language is to use “old words.”

ChatGPT is a mirror that shows us where we’re at. I think what we don’t like is ourselves reflected back at us. It really unsettles us that when the robots say that they’re talking like us, they sound like crappy politicians–that’s how we all talk now!

Jane, could you say more about a point you made earlier: it might be good for a college course to, say, show ChatGPT on a screen in class and say, “Hey guys, this is bad writing. Don’t you guys all realize that?”

But when it comes to high school—where you have on-the-ground experience—you worry that students won’t be able to see that is the case, precisely because to them, adults talk like ChatGPT.

Jane Wageman: I was thinking about that as you were talking, Bo. And one of the problems is that we’re thinking about writing—about an essay—as an object the writer produces. I think, as an object, ChatGPT would look good to a lot of high school students—it’s writing in complete sentences, without grammatical errors, and in a fully-formed essay—so students would see it and think, “that’s what I’m trying to get to.”

Ignore the fact that the thinking is not original, that the sentences are not unique or personal to them. It’s creating the product and if that’s the whole aim, then what it’s doing seems appealing and fine.

I’m interested, then, in thinking about the form of the essay. Instead of being the end product of what you’ve been thinking, with fully polished and solidified ideas; I’m wondering what more process writing would look like for students. So, instead of writing to make a point, what would happen if we prompted students to chronologically walk through what they were thinking, how that thinking changed, written more like a narrative? That would be a way of getting at the uniqueness of how you’re thinking rather than imagining writing as the last thing you do after you have figured everything out.

Bo Bonner: Yeah, an essay is a narrative witness of where your thought is now, rather than the manufacturing of a product to be sent forth for use. Something like that. Renee, moving into your world of editing and reporting, I think we’ve all read copy that’s “just copy,” right? And then we’ve read reporting where we’re like, “Oh, we see the human element in this reporting.”

Renée Roden: Okay, let’s see if I can tie these things together. I was really struck by what you said, Jane, about more of a need for process writing instead of product writing. It sounds like what you’re calling for is a bit like the practice of journaling.

And I’m thinking before computers—someone can fact-check me on this—but before word processors, it seems like most people’s writing form was primarily epistolary. Most people wrote letters, right? And letter writing is a form of writing that makes so much more sense to be literate for.

Why do students write? They write for school, and they write for work, but where in our daily lives are we sitting down and composing letters to our friends? The goal of writing was to be able to communicate with people.

As for journalism, your idea of process writing made me think of the explosion in podcasts and how audio reporting has become so popular. A lot of journalism in reported podcasts follows the reporter through her process of reporting.

Jane Wageman: Sometimes a lot of news podcasts—I’ve noticed this as a trend now—even include unnecessary audio of the setup process or from when an issue came up with the Zoom call. They include the mic not working or the lead-up to the intro to the interview partly to show: “that’s what our process was getting this,” and partly to show these little human elements. It’s not just this polished form at the end.

Bo Bonner: The digital has people really yearning for “authenticity.” I often tell people to be very careful with that word. Authenticity very quickly gets perverted into nostalgia and all other sorts of things.

The digital makes people think that they can find something more authentic than the “polished story.” And so the editors go: give us some more authenticity, STAT! And what do people do when they think you need to be authentic? They talk. There’s something about oral reality, about talking, that even in this very digital age, built on the foundation of a very text-dominant age, many of us default back to the feeling that talking is uniquely authentic. So, even in high-production movies, we’ll have voiceovers or shaky cameras with field noise or what have you, but it goes back to our assumption that orality—to y’all’s point—seems unpolished.

Of course, the most polished of us know when to be unpolished. That’s a sort of rhetorical trope, as old as Quintilian, you know?

Renée Roden: Yeah, that’s interesting.

Jane Wageman: Is that because it’s oral or do you think that’s because it’s easier to attribute a specific human and a specific person to the ideas they’re communicating? Versus writing, which is more abstract—you can’t see who wrote it. You don’t know if it’s one person or many, or a group or a machine. I’m sure there are things that can reproduce human speech, but if you’re seeing someone talk, there’s more of a feeling that it’s tied to a specific person.

Bo Bonner: I think those are the same point. I think what you just said is why orality matters. Renée, sorry, I interrupted.

Renée Roden: No, I agree. About this question of authenticity: originally, if I want to say something, I sit and say it. If I want to tell a story, I, the storyteller, tell you.

And—exactly what we’ve all been saying—the more that writing becomes a technical process that’s divorced from human communication, the more we yearn for the human again, for authorship, because originally that’s what writing is intended to do—to create this interpersonal communication.

And I do think, for the journalism piece of it: there’s this whole sort of crisis of objectivity that’s come up. It’s a problem with the U.S. being many communities that have many sorts of norms and standards. That’s part of the conversation.

There is also this conversation that asks, “Wait a second, is the most factual report one that’s standardly delivered as robotically as possible?” “Is the empirical robotic gathering of facts as truthful—as helpful for me getting to the truth—as much as someone who is diligently, cautiously, and very critically examining a problem and telling me what they saw, knowing that their perspective is limited in scope?”

Bo Bonner: And, immediately, something very new and very old is brought up: on the one hand, ChatGPT and the people who like that stuff. They think they’re actually getting more authentic truth because they’re removing human emotions and subjectivity. It’s a sort of Star Trek/Spock assumption. The idea is, if you just eliminate all this human “fluff,” what you’ll have is “the truth,” and, weirdly, that’s what AI is supposed to teach us, right?

But that’s not what happened with ChatGPT! Mostly, ChatGPT replicates fluff, which is hilarious, but we can get to that later. The other point is—this is as old as Socrates—the poets in oral cultures use the fact that the audio/oral format seems authentic to trick us. Sophistry is part and parcel of orality. You can be just as inauthentic talking. In fact, you can abuse this perception because being face-to-face seems more authentic. If you’re going to lie to someone, lying to their face is the best type of lie. Because you think, “Oh, they wouldn’t lie to my face!” The best liars know how to be authentic liars.

All of this goes to show why in all of these mediums, there is a way you use the medium instrumentally to objectify humans, and the medium, to make it manufactured. Alternatively, there’s a way you do right by it, where the medium is an extension of ourselves, a part of human faculty and capacity.

But this is where we’re at: any problem that someone has in education with ChatGPT, they should have been talking about twenty years ago. But ChatGPT seems to be this big occasion! It now appears is a big enough deal that—this is where I get to be hopeful and have a cautious appreciation of the chat robot—it’s going to make us have conversations. It’s a mirror that makes us look at ourselves.

Jane Wageman: Okay to go back, Renee, you asked about writing versus reading. Reading is affected by ChatGPT too. You can ask ChatGPT about a text in a way that you can’t with Sparknotes. You can be in dialogue with ChatGPT. Both risk replacing reading if a student views them as something that can tell them about what they are supposed to have read, but ChatGPT creates an illusion of conversation.

Or, even if the student has read, she can type in questions to ChatGPT. I’m curious what that does to reading instruction if the way that you’re thinking through a text is by being in dialogue with a chatbot instead of with another person.

And again, if the goal is to come to class with the best interpretation and to be able to share that interpretation with the class, then it’s hard not to see the appeal of ChatGPT. But if the goal is for the class to work through our thoughts about a text together, then ChatGPT is no longer a useful tool. Because coming in feeling like your ideas are already fully baked interrupts that process. It’s harder to have a good conversation if you think that you’ve already figured everything out.

Renée Roden: If a student sat down and talked to another student and said, “Shoot, we were supposed to read Anna Karenina, can you like fill me in?” That would actually be authentic learning, because then that student would translate to that person however Anna Karenina appeared to them and how it impacted their subject.

Jane Wageman: You would be getting that one consciousness instead of imagination of the whole internet.

Renée Roden: It would be—back to Bo’s point—actually authentic because it would be as if that student were imparting not only the bare facts of the plot but also an authorial gloss. It would be actually what language and writing are for, which is to impart an idea and experience to another person.

If ChatGPT were a Cylon from “Battlestar Galactica,”—a fully authentic consciousness with their own ideas and feelings—then that would be great to dialogue with. The problem is that you’re actually dialoguing with Spark Notes.

Jane Wageman: Plus, you’re stuck with the limitations of what people have already thought of. I’m thinking of conversations that have happened in my English classes this year and a couple of times where students summarized part of the text for the class. One of my students gives the most hilarious summaries of things because they’re accurate, but the language that she uses and her reactions to things are very particular to her.

Her views on Jane Eyre and Mr. Rochester and their relationship are relatable but are also very particular. You know, you’re not going to find that if you’re just averaging what other people have said.

Bo Bonner: This is great. So, look at how we wanted robots to be and how they actually ended up. We invented C3PO—who wouldn’t want to ask C3PO about the Odyssey? Even Hal from 2001: A Space Odyssey, what a trip to hear his thoughts! We imagined personalities they didn’t end up with.

Actually, what AI robots are is like a fly going into a bottle with a model ship. Once it goes in, it can’t get out. And that’s the worry about ChatGPT. ChatGPT is just the tomb of language spoken thus far and the average of all of it.

If we keep only talking to ChatGPT, language becomes dead. Having a living conversation continually with those past humans who have gone before is akin to fermentation. It’s dead words, but they spark new life. There are only two options regarding “old words.” Is it a closed system, in which the dead just keep rotting, or is it fermentation where something new can come about from what went before? Is writing then simply a static product, and education the mere teaching of conclusions?

Jane, we’ve talked about this a lot, it seems like education is often reduced to job training. Humans are reduced to conclusion machines: you stuff your brain with past conclusions, then you output “new” conclusions, and that’s all education is.

Or—to nod toward Newman—is education, is learning, good for its own sake because it’s just good for a human to learn things? Just to do it. Just to talk. Just to read. Even the news!

People say, “You need to be informed so you can . . . .” I never know what people think you’re supposed to do once you learn the news. It’s actually because it’s just good to know. And this goes back to Aristotle: humans delight in knowing. It’s internal to who we are. And why wouldn’t we want kids to do that?

ChatGPT ruins that because it gives this impression: that the end of all of our efforts is to make something, to make an object. People worry about plagiarism, but in teaching kids myself, I’m like, “You know, you can cheat all you want, but the minute you do that, you eliminate all the benefit of an education, which is just that this is delightful on its own.” And I know they will think I’m some sort of weird fuddy-duddy that’s lying to them, because they’ve never themselves enjoyed doing it, but I would say, “that’s because you’ve never given it a chance!” Because they think of it as, “How do I get done?”

And just imagine if we did all sorts of things like that: if eating is just getting calories, then eating’s no fun. If sex is just propagation of the species . . . . I mean, you can make anything not fun by reducing it to “humans are utility machines that have tasks to complete until they’re dead.” And we’re doing that with education, and ChatGPT is just really good at completing the task. We’re also probably sort of envious that the robot does the task better than we do!

Renée Roden: I do love that all of our conversations about ChatGPT circle around education, for the most part, because I think ultimately the terror is not this robot that’s not even as fun as R2D2 or Wall-E. The terror is what the robot does to us. What the output of the robot does to our internet, to our brains, how we become less authentic or less personal. We join this mob of data that’s used to create an algorithm and then used by the algorithm to create language. We get dumbed down by looking at it or interacting it or reading things made by it.

I wonder if education is the last sort of “subsistence work” that we have to do to be human. So much of what it means to be a human is just clinging to the face of the earth and trying to make it good. That’s what it has been for so long, and we’re so divorced from subsistence living. But education is actually the process of making yourself a human. In the United States, most of our animal needs of staying alive are met and we are tasked with making it fun. I’m not saying this well. But I almost wonder if we have too much leisure. So, I want to get my education done with and over with and complete the task so that I can have leisure. And it’s like, well what’s your leisure? Watching a ChatGPT romcom on Netflix? You know? Our leisure has become so empty.

I almost wonder if it’s because education is meant to be leisure: a fruit of survival that we can then enjoy and live into. But education has really become the only work so many students are doing for the first eighteen years of their life.

That’s not true entirely. Some people have jobs and then go to school. But education is a certain class of people’s full-time job and that kind of inverts what education is supposed to be. It’s supposed to be this beautiful use of leisure time.

Jane Wageman: Yeah, you’re trying to get it done, so what is your leisure time actually for? So, to your earlier point about letter writing, I think that is something that extends out of classroom learning. If we’re thinking about it, the goal of education is actually that you’re having, in writing or in conversation, these kinds of back-and-forth conversations with another human being and that there’s a joy in that exchange.

And if you’re going to have that exchange, you need to have some kind of shared starting point to talk about. If you don’t have a shared text or shared topic that you have a deep understanding of, then you have a shallow conversation, which is inherently not pleasurable.

It makes me think of Sally Rooney’s novel, “Beautiful World, Where Are You?” and the email exchanges in that book. Some people criticized the email exchanges in that book as not being realistic—that people would not exchange such long emails. I think we talked about this before, Renee—or maybe it was someone else . . . did we talk about this one?

Renée Roden: I think we did. We did talk about it this summer.

Jane Wageman: And those are emails that I relate to, and that people do exchange.

Bo Bonner: You both have been on the bad end of a long Bo email . . .

Renée Roden: It’s true.

Jane Wageman: So here’s another thing with the purpose of writing. One is to have this exchange with another person, with letter writing or writing to a broader audience.

Then there’s also the private journal or writing that’s not actually for someone, but where the purpose is turning over your own thoughts. You are either writing for the sake of thinking through how you’re going to explain these thoughts to somebody else later on or because that’s part of your interior life.

Both of those, though, are writing as a process without a clear end, even though you might be coming to conclusions. It’s like this ongoing conversation that even if it ends at one point, can be picked up again. Or if you’re journaling for yourself, it’s this ongoing formation of your interior intellectual life that doesn’t just have a stopping point. Turn in the paper, get a grade, now it’s done.

Bo Bonner: It’s for its own sake. Like, why wouldn’t you want do that? Right? People say: “School needs to be about teaching kids practical stuff,” and they’re always meaning paying taxes or blah blah blah. And I’m all like, how about having a conversation or being funny for its own sake? Because those things are delightful?

What I’m getting at is, you know, even in terms of teaching them to write, it’s all first about speaking and listening. But that’s hard for students to do, too! We live in an age, folks, where we have made leisure a job. Like how have we screwed that up so bad?

There are three things that I’m always amazed we’ve figured out how to screw up. We’ve screwed up sex being something wonderful. How do you do that? But we’ve pulled it off. We’ve screwed up leisure as actually leisure. We’ve made it a job, intertwining various anxieties into leisure. What the hell is our problem? And then, most basic, we’ve screwed up communicating—the thing that we do uniquely among the other beasts, and we ran it into the ground!

If original sin is not proven in our fumbling those three things, I don’t know what could count as proof, especially as education is supposed to be the crown jewel of a civilization. You presumably do all this other crap involved in human affairs so that your kids can do nothing for a decade and a half but learn. We’re supposed to be proud of that, right? At the end of time during the final judgment, we’re supposed to be able to gloat to other ages, to spike the football, to say: Yeah, our kids did nothing. We didn’t put ‘em in coal mines. We didn’t make ’em dig potatoes. We just let them learn.

And everyone else throughout history will envy that! Instead, we’ve made it a job. We’ve made a production line to make them hate the very thing that should be the pinnacle of all this. It is insane that we were able to pull this off. It goes back to the imperial reign of that Babylonian whore, utility, and allowing it to govern all things, instead of asserting there are just things that are worth it for their own sake.

For instance, a wonderful conversation like this with you two!

Jane Wageman: Bo, I feel like you have had several mic drop, that-is-the-end-of-the-conversation moments.

Renée Roden: Conclusion reached. Conversation over.

Jane Wageman: Not to be continued. Product obtained.

Bo Bonner: On that note, people should know we’re not going full Wendell Berry. We’re using Zoom. The Zoom robot will make a transcript. And we can make a Google Doc. I’m all for leaving it in the form of a dialogue.

Renée Roden: Yeah, I think that’d be lovely. We should just edit it down to a readable length. And get rid of the “ums.” Make us sound pretty.

Bo Bonner: I thought you guys wanted to be authentic!

Jane Wageman: I’m curious what ChatGPT would produce if we asked it to do a conversation between three people.

Renée Roden: Ohhhhh my gosh.

Jane Wageman: On the topics that we have.

Renée Roden: Hold on, my internet robot is failing. Yes, let’s put this transcript up on a Google Doc. And then, we can turn the themes that are distilled into questions for ChatGPT.

Bo Bonner: It’d be curious if it’s like—better than what we write, and we’re like, “Ah, crap!” [laughter]

Jane Wageman: Bo, do you need to run?

Bo Bonner: Yes. Blessings, everybody! Thank you.

Jane Wageman: Enjoy the day.

Renée Roden: See you on Google Docs.